Let’s say you hop on NiGHTS into Dreams… like I did on that Best Buy demo back in 1996–much like Sonic the Hedgehog, it was the kind of game that could catch my eye across the store–just the screen moved unlike any other game on display. Though, at a glance (and honestly, even after completing it), it’s easy to not fully realize the game’s deeply resonant underlying narrative, an experiential story–you feel it, and while playing the HD re-release, I’m beginning to realize that’s what has created such an intense fan following over these years.

The very first time you play the game, it’ll be pretty disorienting. The camera swoops down on a mirror-flipped fantasy landscape. A tiny arrow points your child towards a jeweled, gazebo-looking thing.

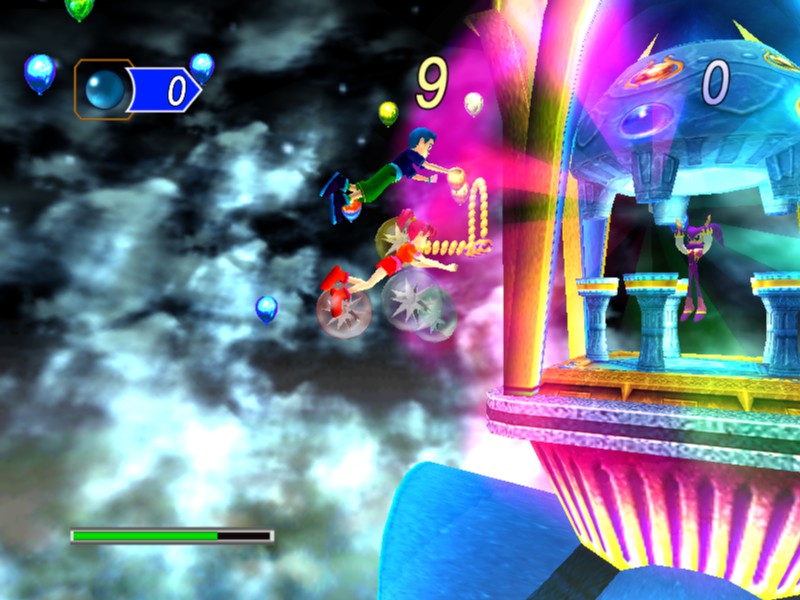

You follow the arrow, but get assaulted by colorful, flying, Cirque-du-Soleil-inspired creatures who steal what look like gems from you. After your sudden, awkward loss, you continue to follow the arrow until you reach your destination. Upon entering it, you take on the form of some sort of airborne jester held within it, and couldn’t possibly anything but curious at this point.

This all happens so quickly that it might not even register consciously. Subconsciously, though, this is an incredible hook: internally, you have to ask: ‘Where am I?” “I did what I was supposed to do, clearly, but I was interrupted–something was taken from me. That was mine…” “They were jewels, so they must be precious…” “Creatures flew away with my precious something… and now I can fly. I must be able to get them back. . .”

The following is never explained in detail in-game, but it is “felt”: these creatures, these nightmarens, actually stole four of your five Ideya’s: Purity, Wisdom, Hope, and Intelligence, but they could not steal your Courage. And you navigate your Dreams as NiGHTS, the Nightmaren you become when you enter the Ideya Palace, to recover these fragments of your scattered psyche. You endeavor in your understanding of the Dreams/levels, and grow alongside your character’s courage as you grow in your wisdom that will allow you to defeat Wizeman, your ultimate villain, together.

After endeavoring through three levels, you reach the final Dream, and you’re unable to reach the Ideya Palace this time; you attempt to enter, but you are thrown away and find that NiGHTS itself is, in fact, trapped in that palace. Now you, stranded on a platform on your lonesome, without that which you’ve always relied on, see that same little arrow pointing you to the open sky. If you don’t take this leap of faith, you’ll be trapped within this Dream. If you do take the leap, you fly. You’ve reached the climax of your journey: you no longer need NiGHTS to go into your into Dreams; you can do this as your waking yourself. Your ability to conquer your struggles is, in fact, something you’ve had all along.

You free NiGHTS. You enter the final confrontation, and now you, fused again as NiGHTS, but with the knowledge that you are one-in-the-same, deliver the final blow to Wizeman. You have grown in your wisdom and are, in fact, now wise enough/experienced enough to overcome that which tormented you.

Then, even with that out of the way, the continued score attack portion of the game still plays into the metaphor. The course-based level design and linking combo system unravel layers of depth in repeat plays to create a sensation that other media can’t: “I’m still not sure I’ve actually discovered everything here”. It makes the game something that you never truly feel finished with, something you can’t stop thinking about–that combination of exploration, discovery, achievement, and metaphorical wholeness makes it impossible to mentally let go. Even score being determined by letter grades and points may seem to fall outside of the compelling metaphor, but the cutscenes of the children’s personal struggles (that depict them being judged in an audition and achieving the higher score in basketball) successfully tie even the game’s ranking system into the metaphor.

This game forever remains in the back of your mind, because it effectively is the human mind, what triggers dreams and creativity, what they’re for. It’s a fantastic emulation of our world, our lives, the concept of endeavoring through struggle and growing into wisdom as a human being. Resonant, engaging, and lingering, just like any good art should be–you can pen metaphors, and clearly, you can code them as well.