|

cre·ate verb \krē-ˈāt, ˈkrē-ˌ\ Definition of CREATE transitive verb 1 : to bring into existence <God created the heaven and the earth — Genesis 1:1(Authorized Version)> |

I wish I was never taught that creation is essentially pulling things out of ether. It was specifically a part of my religious upbringing, but I probably would’ve been organically trained into this mindset anyhow. I should think of this as more American culture’s fault, or maybe I can straight up blame Mr. Webster himself.

But, then again, maybe I should just stop looking for someone to blame. The religious don’t necessarily need to discard their Father, but I do think the artist should be looking to different channels for artistic parenting; human beings can’t conceive from nothing. We deconstruct, abstract, and make clay of what we understand and experience, then we mush stuff up, recompile, craft, and mold–we reconstruct.

It might be stronger and, perhaps, more farsighted to think of creativity as transformation.

Those “crazy noises” during Jimi Hendrix’s famous rendition of the Star-Spangled Banner are fighter jets buzzing overhead and planes dropping bombs. A little research and voilà: he spent a few years in the military–that solo, that interpretation of the song came from somewhere (That also might reveal what got people so riled up about it back in the day: “National Anthem or War Song?”). Absorbing something and then transforming its presentation, ordering, and perspective doesn’t just make music fantastic: it’s the core of what the idea of music is.

The pace of a beat–or the perceived pace of a beat–is relative to the human experience, human footsteps, the human concept of speed (Nobody can run as fast as DragonForce, right? And it’s rare we ever do anything as slow as Sigur Rós). This is metaphor.

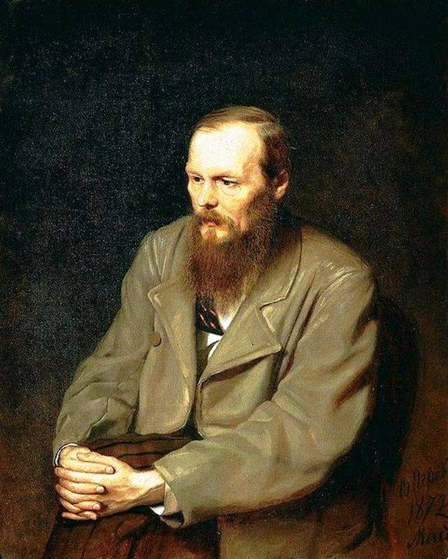

Dostoyevsky wrote of Russian politics, Hemingway wrote of bullfighting and war, China Mièville writes with inspiration from his days of Dungeons and Dragons–it’s important to be honest and open to our sources of energy. To embrace, absorb, and understand them.

Given that, writer’s block could be considered a sort of false disease; it might have a great deal to do with a failing understanding of what it means to be creative. That classic image of a writer curled over his desk in isolation: “you toil and toil yet can not produce! Oh woe is me!”–you can’t put out if you don’t take in, and you can’t take in if you only put out. You need to go outside.

Hemingway was a journalist before becoming a novelist. Dostoyevsky ran in political circles and even went to prison for it. China Mièville is never shy about his sources of inspiration. His favorite pastimes come up in nearly every interview, and the man actually ran for parliament.

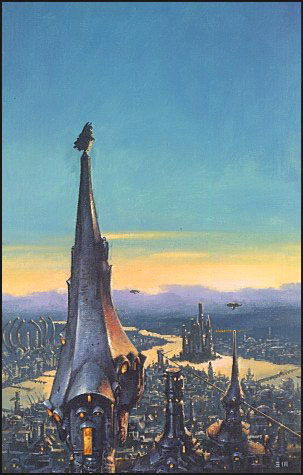

Video games aren’t exempt from this either. Super Mario is the classic knight in shining armor story: Mario’s the knight, and Yoshi is his steed; he goes to fight the dragon Bowser and save the Princess Peach. This is Super Mario’s foundation, but, I mean, look at it. When you open yourself up to soak in just a little bit more, when you hold yourself back just a little bit less, that core foundation becomes something more: you get a game about a guy who walks on clouds and travels through pipes because you like manga and pass sewage systems on the way to work.

It takes absorbent and free minds to make flying via a raccoon tail seem unquestionable. It takes adventurers, it takes listeners, it takes people who aren’t going to question how they got there until they get there, people who only look back in order to figure out how to go forward. It takes creatives.

And all of the above, at least as far as I understand at this point, is the source of the Voodoo. It’s what we need to do to watch the sunrise from the bottom of the sea. And as long as I think like this, I never seem to become stuck, more like:

“I’m not quite yet where I want to be, but getting there is fantastic, and hey, here’s everything I’ve found along the way. There’s more coming, and it’s only going to get better. I hope everyone’s having a good time.”